Hello from the place I grew up.

The sentence reads as inane, but my guts are in my mouth as I write it. But then, I guess not everyone feels the urge to escape the place where they were made. Not everyone finds coming home so bewildering.

In the weeks since I arrived, I've observed scores of my fellow citizens acting out their routines unremarkably, and sensed in myself an inexplicable, mounting panic. People jog past me, chat with friends at coffee spots, zip to and from work, and I realise that there's a deep, fiendishly wounded part of me that wants to scream:

Do you know what it was like for me to grow up in this place that you are so lavishly enjoying? Do you know that I moved my entire life to another continent in order to feel that I had room to exist? Do you know how good you have it, that you grew up here feeling that this place was designed with you in mind?

Phew. Intense, no? Very main character energy. Of course, this is a complicated knot of projections; such hostility towards my fellow city-goers is profoundly unfair. Being back here makes me anxious, and there are clearly some hurts to be healed.

And lately I've been pondering this healing, the mechanics of it, what steps I'd need to take to ensure the simple act of being back in the place I grew up doesn't intermittently flood my nervous system with dread. So I have thought big thoughts, journalled, and roped various friends into weighing in on my woes. And the question I've been left with has arrested me.

If you run away from home, can you really heal from afar? Or does the healing only happen in the homecoming?

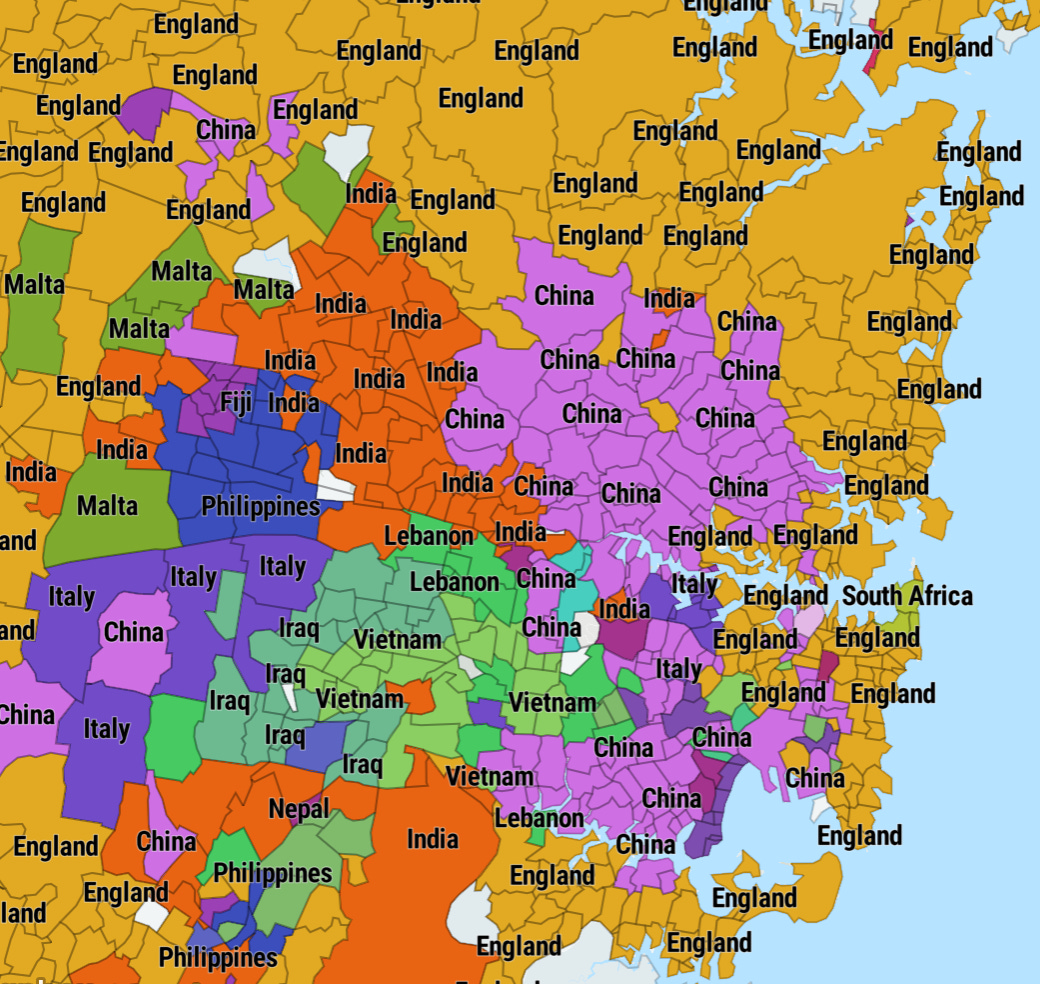

I grew up in the Northern Beaches of Sydney. These are the most north-eastern suburbs, existing almost as their own enclave, and as they stretch further north the beaches become more spectacular, the people become wealthier, and everyone is really fucking white. It is an upmarket, upper-middle class area, and many people who live there feel no need to stray from it - I remember a schoolmate of mine proudly sharing that he'd crossed the Sydney Harbour Bridge, which connects the two halves of the city, only once. If it helps you visually, the soap Home and Away is filmed there, and perfectly captures the aesthetics of the place. It also has the lowest rate of obesity, not just in the city, but in the entire country. Go figure.

My parents, both immigrants, settled in the lower, inner part, which was largely more affordable, and far from any beach, albeit still patently middle class. I got myself a scholarship to a fancy private school where I rubbed shoulders with kids who had experienced an unimaginable level of privilege. Their fathers were inattentive, C-Suite types, their mothers engaged in the strenuous labour of maintaining their rich white lady glamour. Speaking of whiteness, there were few kids of colour in my grade, a smattering of international students, myself, and one or two others. We were all so intensely concerned with the urgency of our assimilation that there was no sense of solidarity between us, I'm not sure we could have even conceived of a thing. No student in my time at the school ever came out as queer, in fact gay bashings were not an uncommon occurrence in the area. I was also the fattest kid in the school for a good portion of my time there.

To that particular school in that particular part of the city at that particular time, I was an emblem of some of the least understood and least desirable aspects of being human. And this is how I was treated, in the way that you're probably imagining, by students and, less nakedly, by staff. It wasn't always awful - I was handled with as much curiosity as I was contempt. There were moments of staggering brutality, and moments of welcome reprieve. It was, though, consistently very lonely.

The memory of this experience, and the traces it left within my body and psyche, was what I escaped when I decided to leave Australia in my early 20s. At the time, I dreamt up a story about a big adventure. But really, I was fleeing with abandon. I needed room to breathe, a place that was not so humid with the spectres of my youth. I needed to put myself back together, away from the threat of dissection.

And so I did. And since then, a decade and two other countries I've called home have whooshed past. In many ways, the Great Escape™ has been a roaring success. I stepped into the space I granted myself, I found people whose experiences mirrored mine (many of them also taking refuge from the stories foisted upon them which they had no choice but to metabolise) and I felt the cleansing wash of kinship, of another family, of community. I fought hard to find some resolution to the distress that had marked me, to chew through the gristle of the worst of it. I began to heal.

But for many years, when I returned to Sydney to see family and treasured friends, I couldn't help but interact with the city in a disordered way. I sought out a continuation of the narrative I'd scaffolded - that my retreat was justified by the inherent hostility of this city and its residents to me, to people like me. I walked around the streets blind to the fact of whatever was happening around me, transfixed by my own sumptuous fiction, seeing a caricature of the city forged by my suffering within it. I had been healing away from my pain, not towards it. And now, any step back into the home that had betrayed me felt completely obliterating.

When I first read Jenny Odell's essay collection How To Do Nothing, I felt something shift in me. To this day I quote it constantly, in fact I'm sure my friends stifle an eye-roll every time I find an excuse to bring it up. The book is about the attention economy, listing out the nefarious ways our digital technology seeks to capitalise on our attention, and her various strategies to harness and direct her attention to the places she wants, rather than the places said technology demands.

In the book, Odell talks about the impossibility of retreat when it comes to these new technologies, that to give up, say, social media at a time when it's become so baked into the fabric of our world, often comes at a cost that one can't always afford. Instead, she advocates for a kind of refusal-in-place, to partake and be present in these attention-demanding contexts while simultaneously refusing to play by their dictated rules. She suggests that when it comes to these technologies, not retreating, but instead staying put and reclaiming your agency, is an important form of resistance.

The first time I read this I instinctively transposed what Odell was saying into the context of my life. The simple idea that one could resist an oppressive digital or physical environment through mindful, intentional presence, rather than rush to escape, floored me. Escape was what I always did when things were closing in, I escaped into books, escaped into my imagination. In the end, I escaped to a different country. What if in my life I had instead refused-in-place?

When I think of the anguished child who left Australia a decade ago, I see that all he knew, all he had within him, was escape. I would not be the person I am today, a person who I feel a lot of affection and tenderness for, had I stayed. I do not think I could have made the rules of the place I suffered in bend to my will. Even if I'd had the imagination for it, I'm sure I would have crumbled in the effort.

But I am not that child anymore. Ten years on, I walk this city as a visitor and see that there is the opportunity for me to redraw the narrative I have hung upon it all of these years. I am enticed by the pockets of queer resistance across the city that I see bubbling up. I see an observable increase in the visibility of Black and brown people on screens, in elected office, around me, even if it still feels like it's not enough, like this country is lagging behind. And there are other considerations. The new babies of my loved ones are proliferating, my parents are getting older - the years are beginning to distend with more meaning, and generations are turning over. The more I am away, the more I miss.

But above all, how heartbreaking it would be for one's life to be a series of withdrawals, of movements away from a foundational hurt. I have been running away from home, and I have not stopped to take a breath, because to stop would mean to take in the enormity of what I'm running from, how exhausted I am, and how little ground I've really gained.

I have come to accept that the option to escape was inflicted upon me, because escape was my only chance of liberation, of rebuilding my life. But there is a difference between being moved to leave, and choosing it. There is a dignity, a luxury in choice.

I want to choose.

An old friend has just bought an apartment within walking distance from the beach, and I drive over to help him and his partner move in. My help consists mostly of watching them unpack boxes and playing with their infant daughter, who is radiant and captivating and meeting me for the first time. They wipe down surfaces and dress beds and I let her little fingers grasps the masts of mine. Eventually we all decide to wander down to the new beach on their doorstep, traipsing the hills of Sydney suburbia and setting up in a shady alcove under a sagging tree. I walk the sand towards the water and it's cold on my feet, despite the sun. Still, I rush into it, like I was taught, on the beaches I grew up on. I am dodging bluebottles and tufts of seaweed expertly, slipping over waves without thought, surveying the surrounding cliffs. I take an easy breath and slide under the surface of the water, let the air snake out until the bulk of my body sinks me down and I am adrift on the ocean floor, silent, relinquishing my movements to the tide. I have done this since I was a child, a little gospel to the ocean, my ultimate escape. When my lungs bristle with the effort, I plant my feet back underneath me and propel myself up like a piston, breaking through the summit of a wave that curls over before gently setting me down.

My eyes adjust and for the briefest of moments I see this place, this city, for what it is, unencumbered by the weight of my projections, traumas that have calcified into opinions. I see the miraculous sun and the people thrown out like freckles on the shore, and for a few seconds, I am not a fat, brown, queer body in a place that is trying to destroy me. I am simply a body in a place. And this place is beautiful. Even more for the fact that I am in it.

And when the moment passes, as it must, the salt water welling within me falls to join the salt water around me and a rigid, well-worn part of me unclasps, lets go of something that was held.

I am ready to stop running.

I am refusing in place.

Oh my, this was such a gorgeous exploration of the meaning of home and place and I am very thankful I read it. 🥹 this sentence especially flooded me — “I see the miraculous sun and the people thrown out like freckles on the shore, and for a few seconds, I am not a fat, brown, queer body in a place that is trying to destroy me. I am simply a body in a place. And this place is beautiful. Even more for the fact that I am in it.” — immediate subscribe!

.. beautifully written, I resonate a lot with this piece. I feel like an alien returnung to my home town in the "bible belt' (central valley) of California. I have been escaping since college - LA, San Diego, Detroit, New York city. I am now a therapist/ social working and am wondering if my choices to help others for twenty years is a sophisticated trauma response from my childhood experience of being 'othered' I am not sure I'll ever gain a feeling of 'home'. Am I exploring or running by losing myself in the stories of others and never putting down roots?