Displacement

Short stories about leaving

I had never met my landlord before yesterday, only his older brother, who is cheerful and avuncular and once brought me a 2 litre vat of olive oil straight from his farm. The man I have been paying a small fortune to every month trundled in with his wife, another brother, and a cabal of relatives, who spoke to me in an American-inflected English, launching into stories about their emigration to New Jersey, how much they hated the orange man, but how much they hated Portugal too.

We are a good people, but there is nothing left for anyone here, his wife said to me sadly, gesturing to the floor. Even our kids don't want to come here. But have you enjoyed your time in Portugal?

My landlord smiled weakly and didn't ask my name. I guess he already knew it. He seemed like the kind of man who could get away with sidestepping pleasantries, whose world bent around him to ensure his safe passage. He surveyed the space with an easy precision, the tongue of the measuring tape never leaving his thick hands, and asked me to move out of the way, more than once, not unkindly. The porteira once told me that these three brothers had grown up in this apartment, that their mother had gotten very ill when they were of university age, and two of them had left to the US to seek something better. I felt like I had been told something private, some family history I probably ought not to know. To move across an ocean in order to make something of yourself is an exposing act. I know it well.

I watched as they discussed renovations to come and fidgeted anxiously from my assigned corner. My head swam. At once, I had a coarse, dizzy feeling, a feeling of wanting to walk up to the five of them and push myself into their sight lines, to say in a steady and compelling voice that, hey, I was here, I am here, this space was mine too, and you should know that I belonged to it, momentarily. I made something of myself in the space that you left, and you made something of yourselves away from it, and isn't there a miracle in that we should name? That we all became something away from the places that made us?

I made to take a step forward but stayed still, queasy in the realisation of my forthcoming displacement. The space was no longer mine. Really, it had never been.

Sorry for the inconvenience, we won't be much longer. My landlord peered at me as if through glass.

What will I have for breakfast tomorrow, once my blender is gone, once this space is razed of all of the things that made it a home, that made it, briefly, a place where people loved and ate and felt warm in its walls? What will I do when I cleave open my eyes and there are no remnants of me left here, when the little and big things I bought to fill out the swollen space have been packed away, when there's nothing to register a life that was lived except alien imprints, the scuffed squares and rectangles on glossy hardwood floors?

A woman is coming to look at my bed. Earlier in the day we spoke over the phone and I stumbled over the words for bring and take, forgot the word for headboard. I could hear her smiling over the line. I immediately decided to sell her the bed.

She comes and she comes with stories. She tells me about her spectacular divorce, how she left Brazil with her daughter to find solace in Europe. She tells me about Bahia, where she is from, and tells me I should go, because the women will be fighting over me. I inquire about the men and she laughs coyly, and her laughter is bright and hopeful. She talks about her favourite magazine, fetching me her copy from the black canvas trolley she has brought and insisting I take it. She asks for a glass of water and I wince at my forgetting to offer, but she follows me into the kitchen and tells me about how her parents died during the pandemic, quite suddenly, in their 90s. I grimace in her direction, utterly without the right words to express sincere sympathy – but she is smiling.

It was beautiful, she says, they were in separate hospital units but they died within minutes of each other.

I am enthralled. I find myself spilling my life out to her in great cords, my anxieties about leaving, the people I will miss and the people I feel bad about not missing, how strange it has been to pack up an apartment and with it put memories into boxes, how little magic I have made out of the summer so far. She listens and calls me meu querido and takes my hand in hers, and I truly think I might love this Brazilian woman in this moment as much as I love my own family.

It is an hour before we make it to the bedroom so she can see what she is buying and the appraisal is swift. Essa é minha cama, she says with pulsing eyes, and she's right.

When she fetches it that evening, two young guys prising it apart and taking it bit by bit down the staircase like worker ants, the bedroom is achingly empty, and I cannot imagine that there was ever a bed there, even less so that it was ever mine.

A friend takes me cycling along the water's edge, because I am full of vigour for seeing as much of Lisbon before I go, and I like the idea of earning my way to the beach. The day starts grey but flickers into blue and by the time we reach the hungry mouth of the ocean, we are dry in our own salt, pain across my back and shoulders like being pressed into a hot pan. We eat and talk about our lives and strip to our underwear and meet the lapping water.

When we cycle back, our legs whirring and the helmet rubbing skin raw at the tops of my ears, I see the oncoming vista of the city all at once, and for a moment my life feels uncomplicated and singular and I am swept up in the exacting pleasure of moving in one direction, at pace, with nowhere to be but where I am going.

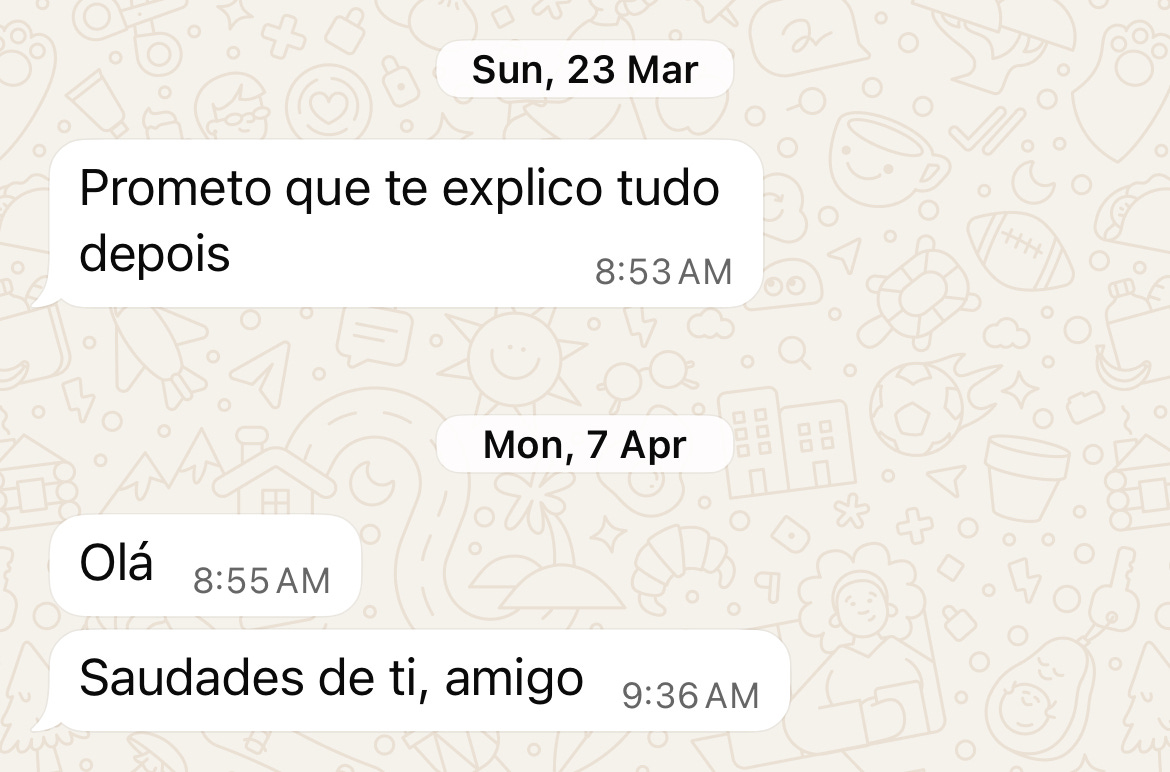

A boy came round last week who I have seen once a year, like clockwork, since I first arrived in this country. He texts me intermittently - Saudades de você, viu? At first I would reply, suggest we meet, and we would both perform limited availability, until one of us folded back into the routines of his life. Then a month later my phone would flicker and I'd see his name again.

Once a year we get our act together. The first time I was freshly single and found his advances overwhelming, wounding, having forgotten the particular bleakness of being touched by a stranger. He was soothing, careful, and when he spoke I caught the smallest hint of sadness, which softened me. After, we had sat in the purple light of mid-winter and I had nuzzled myself into his side as he corrected my conjugations and gender accordances. We were two men who were thoroughly displaced, but nesting ourselves in that particular sofa, even if just for an afternoon, felt like a gesture towards rootedness.

Last week we grabbed lunch at a buffet restaurant, €9.95 each, and when he left for the bathroom midway through dessert, I saw immediately that he was slipping away to pay. I didn't stop him. I knew we would both find some pleasure in the romance of it, the performance that we might mean more to each other than we actually did. My leaving, news of which I had delivered to him over text with the seriousness of a sermon, had enlivened a kind of tenderness between us that I imagined was only surfacing because we both felt safe in its impermanence. We would slip out of this intimacy and back into the churn of our parallel lives within weeks. In that way, we were risking little.

His life, in his telling, is onerous. He works at a restaurant in the tourist district and is always fielding yappy, pink British men on stag dos whose regional English he can't make sense of, or fussy older French couples who expect him to have sommelier-level wine knowledge. He complains about this, about the repetitiousness of the work, about how much longer he has to wait for his European passport so he can go to Luxembourg or Denmark or somewhere he won't feel like he is skimming by on the surface of his own life. I listen attentively and drag my fingers through his curly hair, kiss him between his eyes. I do think it sounds awful. In turn, I complain about the logistics of the move, the impossible frustrations of Facebook Marketplace, cumbersome farewells with friends. He hums and lays his hands on the middle of my back, as if holding me up. Neither of us have the heart to acknowledge the valley of agency between us, that he is staying here because he has to, that I am leaving because I never did.

After our lunch, he came to the apartment and we returned to the sofa we first met on, soon to be disappeared alongside everything else. We had sex, and after, while I showered, he looked over the last dregs of the objects I'd yet to sell or donate.

He took with him two protein shakers, a large metal bowl, a bag of tea candles, a loaf tin and a Portuguese novel I never got around to. He put his head on my shoulder as I opened my apartment door, letting him back out into his life.

A gente vai se ver mais uma vez antes de você ir embora, né?

Com certeza, I said. It translates to with certainty. But the only thing I am certain of is that we have committed each other to memory, and that in a passing moment on a future day, we will think of this spare romance – of our three days together across three years – and we will smile, at the generosity of our performance, of how we saw a familiar longing in each other, and how we both did our best to meet it, in the ways we could, in the moments we found.

Love this x

vai sim